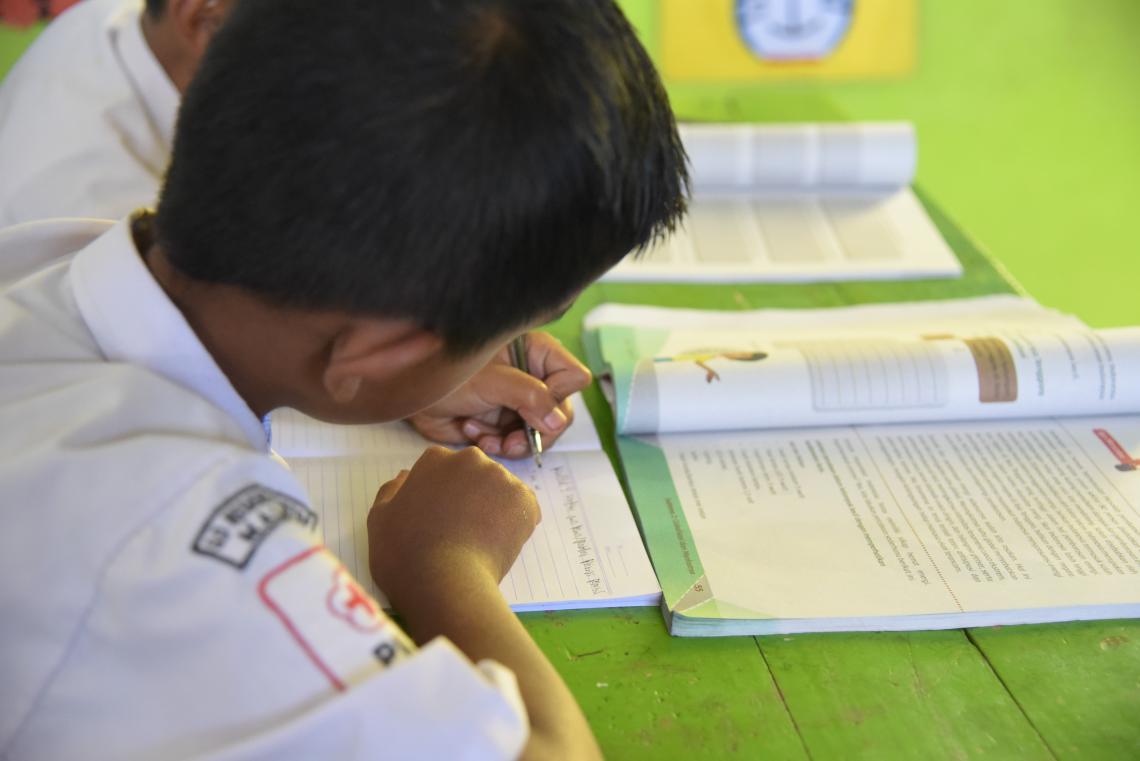

Photo illustration: Novita Eka Syaputri

.

This article was originally posted on The Conversation Indonesia and has been translated by RISE team.

.

After students in Indonesia were forced to study from home for more than one year, Minister Nadiem Makarim appeals for in-person learning to resume.

Around 63% of schools in regions imposing public activity restriction (PPKM) levels 1, 2, and 3 are permitted to hold in-person learning.

Analyses of previous studies, for example, described how unequal and ineffective learning from home results in many students losing their reading ability equivalent to 6 months of learning, and risks to erase demographic bonus and reduce children’s future income.

This means that schools and teachers must first perform emergency measures when school reopens: recovering student learning losses.

The risk of resuming in-person learning without recovering learning losses

Students’ abilities will be much more diverse than before the pandemic as the effectiveness of learning from home varies—particularly between well-off and underprivileged students.

This indeed affects students’ abilities to keep up with learning when they return to school.

Students who struggled mastering lessons from the previous level during the pandemic, for example, will have difficulty comprehending new lessons that require their understanding of materials from the previous level.

Previous research from SMERU found that in 2014, only 35% of Grade 12 students answered Grade 5 math questions correctly—seven levels below their level.

This is likely to get worse during the pandemic.

Without specific means from the school to address this variation, learning losses and unequal learning outcomes will worsen as students’ learning levels increase.

Three emergency measures: Assess, teach, monitor

We recommend three measures that schools and teachers can do to recover learning losses when students return to school.

1. Assess students’ abilities

Schools need to carry out diagnostic assessments in the first weeks of reopening to map students’ varying learning abilities.

The diagnostic can be in the form of questions that test essential materials students have learned before or should have mastered to understand the materials taught next.

Teachers can then use the results of this assessment to provide guidance and further assistance to students in need.

The US Education Office, for example, encourages schools in the region to apply a number of computer-based diagnostic assessments. This series of assessments gauge every student's academic shortfalls in math, language, and science and recommend what material to study next.

2. Group students based on their assessment results

Teachers can use the information obtained from the diagnostic assessment to design differentiated teaching.

That means students with the same ability are first grouped into several small groups. The learning strategy is then adjusted to the level of student learning in each group.

For example, a group of students with assessment scores above the class average may be given normal instruction.

Meanwhile, a group of students with below-average scores—who are likely to be left behind during the pandemic—needs to be given more attention by re-teaching the materials they have yet to understand to catch up.

Beyond this grouping practice, during regular school hours, students in the lower group can still learn together with students from other groups and contribute according to their abilities.

A study in Kenya found that giving instructions in groups divided according to students’ initial abilities significantly improved their math and language performances.

3. Monitor the progress of each group of students

Teachers should gauge and evaluate students periodically throughout the school year to monitor their progress. If students show significant learning progress, they can continue to study new material or be transferred to a higher [ability] group.

To expedite this process, teachers should encourage improving student learning from one point in time to another (often called formative assessment).

Curriculum or teaching materials also need to be simplified so that teachers can focus on monitoring the recovery of these students' learning losses. For example, teachers can temporarily focus on recovering students’ basic skills, such as literacy and numeracy, and other materials that students have not mastered based on the diagnostic assessment.

If this is overlooked, instead of closing the gap in student learning, teachers will again fall into the usual practice of testing students only to meet curriculum targets.

Teachers need full support from the school to recover student learning outcomes

The three measures have been proven effective in improving learning outcomes, especially for low-ability children.

Studies in India and Africa show that practicing the three measures—referred to Teaching at the Right Level or TaRL in research—positively impacts lower ability students to catch up faster.

However, the practice of TaRL in the two regions shows that efforts to recover learning losses require preparations—providing training to teachers alone is not enough.

Teachers need support to understand how to use assessment results in designing learning and clear guidelines on monitoring student progress between groups. But the most important thing [for teachers] is [getting] full support from the school to focus on implementing learning centred on student needs rather than achieving curriculum targets.

With such a supportive environment, practicing the three assess-teach-monitor measures will be effective in improving learning outcomes and recovering learning losses due to the pandemic.