Photo illustration: Novita Eka Syaputri

.

This article was originally posted on The Conversation Indonesia and has been translated by RISE team.

.

So long as the COVID-19 pandemic remains uncontained, distance learning is likely to stay the primary method of learning for many students. The implementation of the emergency public activity restrictions (PPKM), for instance, has caused the government to postpone its plans for in-person learning in schools throughout Java-Bali.

Even in many provinces outside Java-Bali where in-person learning is permitted, schools still have to provide students the option of learning from home or at school due to their different situations. Unfortunately, distance learning has been ineffective and has widened the gap in student learning outcomes in Indonesia—particularly those from low-income groups. It has also caused massive economic losses due to lower learning outcomes and an increased potential of school drop-outs.

The government and schools should continue to develop distance learning strategies so that the quality is equivalent to in-person learning, considering that distance learning will remain during the pandemic and in the future.

Remains the primary option for many students

Due to the increasing number of COVID-19 cases, students throughout Java-Bali must return to distance learning at least until PPKM is lifted.

Some researchers have even suggested that the government should continue to restrict public activities more strictly and consistently until the pandemic is completely under control—making the prospect of in-person learning even more uncertain. However, many students in other provinces are also forced to continue studying at home due to limited in-person learning, or the schools have yet to meet the government requirements.

Towards the 2021/2022 school academic year, for example, the government issued the Restricted In-Person Learning Guideline for primary schools, which, among others, stipulates that at the beginning of the school's opening, only 50% of students are allowed to attend.

Furthermore, on the pretext of enforcing the health protocols, schools can also issue discriminatory in-person quota regulations.

Ahead of preparation of my child's in-person learning, for example, we have to fill in an online form from the school asking what mode of transportation the child will use to go to school. When the answer is public transportation, the system will state that the child must continue to learn from home. This means that many of these students—usually from low-income families or whose parents work—are “forced” to continue learning from home.

Amid an uneven quality of distance learning between regions, the gap in learning outcomes is getting wider for these students. Therefore, developing distance learning with quality equivalent to in-person learning is an absolute necessity for every school.

Developing distance learning equivalent to in-person learning

This development effort requires mutual cooperation of all education stakeholders. Moreover, in the future, distance learning could become an essential part of the school system—either fully or combined with in-person learning. When the pandemic is over, distance learning will remain and should not be treated only as an emergency response.

Numerous internet infrastructure developments in Indonesia that are currently underway will also allow distance learning to be distributed more evenly throughout Indonesia. But, that is not enough.

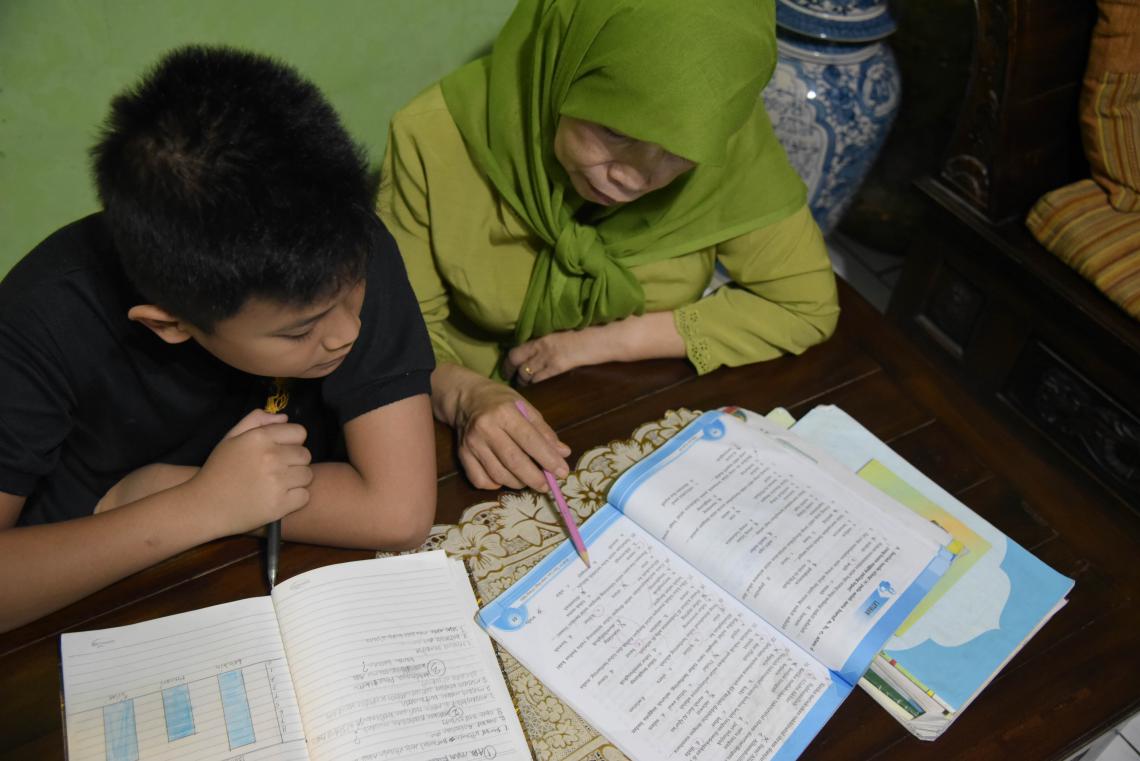

First, teachers as well as parents who guide students are not only required to be fluent in educational technology, they must also understand the different needs of students when learning at school and at home.

Organisations that care about education gaps such as SchoolVirtually, for example, provide approaches and learning plans for teachers using low or no technology—from developing study plans with parents via WhatsApp (WA) to strategies for delivering materials using a school pick-up system. The government can work with such organisations in Indonesia to help students with minimum access to distance learning.

Second, education decisionmakers must also continue to innovate and evaluate the implementation of distance learning.

In Indonesia, the focus of innovations in distance learning has been mainly on online services, for example, the Rumah Belajar platform owned by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology (MoECRT). Offline-based innovations for those with minimum access to online learning are much needed.

The institution with the potential to develop such innovation is the Open University (UT), which has 37 years of experience running distance learning with a variety of students from high- or low-income families, both in urban and rural areas. One of their largest faculties is the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education (FKIP), which focuses more on distance learning competencies. There are more than 128,000 FKIP students or 41% of all UT students this year. MoECRT should collaborate with FKIP Open University and its graduates to develop innovations to improve distance learning in Indonesia.

Third, involving parents is no less important in the development of distance learning.

To date schools have yet to involve parents in their children's education process—parents’ involvement is only restricted to attending school meetings or paying school fees. In fact, parents play a major role in supporting their children's academic achievements while learning from home—a role that is increasingly important during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Quality distance learning, both online and offline, can help students—regardless of their background—get educational services equivalent to the outcomes of in-person learning that we know so far. Indonesia now has the opportunity to make a breakthrough in distance learning. If we maximise this opportunity, we can transform the Indonesian education system to be better and more just after the pandemic ends.

*Heni Kurniasih, institute secretary of The SMERU Research Institute, also co-authored this article.