Illustration: Tony Liong

![]()

-

This article was originally posted on The Conversation Indonesia and has been translated by RISE team.

-

The mounting problem confronting Indonesia in the future is the poor quality of student learning outcomes. If we allow this, the majority of our human resources will not be able to compete globally. This means that we cannot take advantage of the Industrial Revolution, 4.0 which requires a reliable and innovative workforce.

Efforts to improve the learning quality are the main responsibility of the government. However, the government's ability to serve the public is limited.

Therefore, to meet the needs of the people, which continue to grow and change, the government needs to provide space for community initiatives. Government policies must be specific for "building with the people" rather than "building for the people."

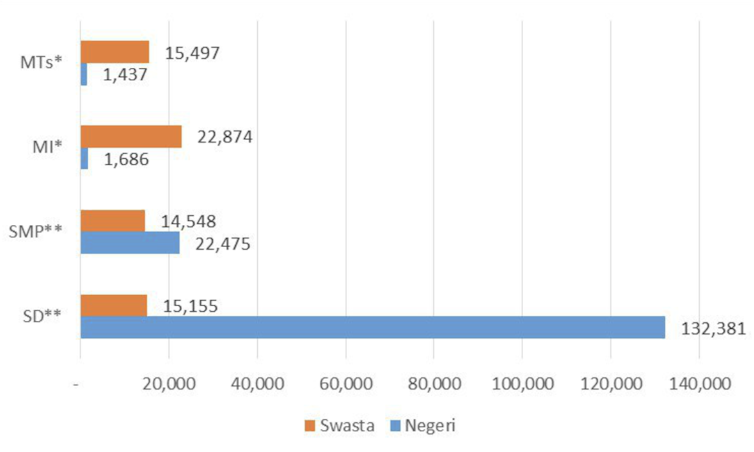

For example, in education, the government can work with the community to build and maintain schools. In this regard, the community's capacity is quite real. As many as 30% of school buildings are built and maintained by the private sector.

Comparison of the number of public and private schools in 2015/2016. Indonesia Educational Statistics in Brief, the Center for Education and Culture Data,Downloaded 10 April 2017.

However, the problem of the quality of learning outcomes for school students in Indonesia is not only about school building facilities. The community also needs to be involved in student learning activities.

Building schools since the Dutch East Indies

In 1983, as a researcher on the Development Policy and Implementation Studies project, a collaboration between the Indonesian Government and the Harvard Institute for International Development, the United States of America, I learned that the Dutch East Indies Government from 1907 had allowed the construction of schools for local residents called the volksschools or people's schools. A year after the permit was issued, the community in an area located deep in a remote region of South Sumatera, now known as Tanjung Agung sub-district, built the first volksschool.

Until 1945, the people of Tanjung Agung had built six school buildings. During the struggle for Indonesian independence from the Dutch from 1945 to 1949, they built four school buildings. During the 1950s, the people constructed nine more school buildings, six of which were state-owned, and the other three were private schools.

In 1972, before the issuance of Presidential Instruction No. 10 of 1973 regarding the primary school building construction assistance or the SD Inpres programme in Tanjung Agung sub-district, 29 schools accommodated more than 75% of children aged 7–12 years. However, nationally, the figure stagnated below 70%.

Along with the government's growing concern about educational facilities, oil production increased, and its price soared rapidly. Thus, the government had the flexibility to allocate the state revenues to finance development, including constructing many primary school buildings.

Since then, almost all school buildings built by the people of Tanjung Agung sub-district in the past were then rebuilt through the SD Inpres programme, whose funds came from the state budget. After more than four decades, the number of primary school buildings in this sub-district had only increased by two. Still, there were an additional six public junior secondary school buildings and two senior secondary school buildings.

The impact of the SD Inpres programme

Before the SD Inpres programme was introduced, people in various regions built school buildings with local capacities. They used timber from the forest around the village and worked together to build a school while parents provided the tables and chairs.

As a result, buildings and equipment varied between schools, but they were generally in decent and well-maintained conditions. However, since the SD Inpres programme was launched, there were no longer public primary schools built by the community.

The programme itself was a great success. According to research by economist Esther Duflo in 2000, the national schooling rate for children aged 7–12 years increased from 69% in 1973 to 84% in 1978. In 1990, the World Bank reported that the figure had reached 92% in 1987. Moreover, since the SD Inpres programme, school access for children based on gender and level of welfare was equal.

Unfortunately, this success also raised two problems. First, the community tended to become "recipient" of development results, along with the disappearance of "social capital" in the forms of responsibility and mutual cooperation in building schools.

Second, the enthusiasm of the government and the community to expand access to schools had neglected the attention to learning quality, whose impact remains to date.

Towards the 1990s, after the oil boom passed, the government's ability to build and repair public primary schools had declined. Since then, even though some school buildings had been damaged or even collapsed, people tended not to care.

Recognising these conditions, several regional governments have tried to return the responsibility for maintaining school buildings to the community. Based on a research from the SMERU Research Institute that I participated in 2001, Kebumen District in Central Java, for example, has approached the community to participate in repairing school buildings.

The Head of Kebumen District visited from village to village telling the people that the regional government only had about one-fifth of the cost of building rehabilitation. As a result of this “build with the people” approach, nearly a thousand classrooms have been repaired.

Software: Learning activities

The purpose of children in school is to learn. However, the quality of learning between schools and between students varies. Therefore, children’s learning outcomes differ from one another, with gaps that are often large. The difference is determined both by the learning process at school and at home. As stated by the former Minister of Education from 1978 to 1983, Daoed Joesoef: teachers should be the second parents at school, while parents are the second teachers at home.

In schools, the emphasis on improving the quality of learning lies in teacher management, which includes recruitment, placement, professional development, and incentives. For this reason, the education sector receives an allocation of 20% of the state budget.

However, according to a study by education policy researcher Joppe de Ree and other researchers in 2017, the large investment in education was not accompanied by an adequate increase in the quality of learning. The majority of teachers who took the 2015 Teacher Competency Test, for example, did not pass the test. Due to the low quality of teachers, it is only natural that the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores always place Indonesian students in the lower group.

At home, parents pay less attention to their children's learning activities. In many places, parents tend to completely leave their children's learning activities to the school because they are busy with daily work, have low education, and do not keep up with changes in their children’s latest learning methods.

Based on the test results of the Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), the academic ability of adults in Jakarta who graduated from senior secondary school was lower than that of adults in Denmark who had not graduated from junior secondary school.

In relation to these conditions, the 2018 Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) in Indonesia study, for example, shows that between 2000 and 2014, the numeracy skills of students attending school at all grade levels actually decreased.

Numeracy skill of students who are in school. Processed based on Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS), Author provided

Low expectation

According to the 2010 research results from an Australian National University senior researcher Blane Lewis, Indonesian people are satisfied with the practice of education services. The reason might be that their expectations of the level of educational services were indeed low. Therefore, the majority of the community has no enthusiasm to respond to the reality of the low quality of student learning outcomes.

Meanwhile, parents who wanted their children to receive good education services would send them to tutoring classes outside of school at a fairly expensive cost.

The community needs to change their mindsets and not be complacent about the practice of education services in Indonesia. Parents need to be more involved in their children's education and fight to improve of the quality of education services in Indonesia. Otherwise, the school bureaucracy will continue to work on a routine basis without any effort to improve the learning process.