The COVID-19 pandemic and distance learning have “forced” parents to carry a gigantic load to be more engaged with their children’s education while they learn from home, despite various challenges.

A study by the Jakarta Provincial Government and the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab Southeast Asia (J-PAL SEA), for example, found that parents had difficulties keeping their children focused on learning, particularly for students in Grades 1–3 of primary school. This challenge was even greater for low-income families due to the lack of access to subject matters, gadgets, and internet connections.

The above is also the reason the Government encourages schools throughout Indonesia to resume in-person learning.

The good news is that a study conducted by The SMERU Research Institute in Bukittinggi, West Sumatera, shows that parents in the area have managed to overcome those challenges.

The majority of parents had high awareness to guide their children regardless of their socioeconomic background. In fact, student achievement in Bukittinggi during the pandemic was higher than the previous year.

This success shows that if parents are committed to being more engaged with their children’s learning at home, the impact is massive on their academic achievement.

However, to build such a high commitment to parents throughout Indonesia, even after the pandemic, require campaigns and strategies from all actors in the education system.

High- or low-income, effective guidance has a massive impact

The Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE-SMERU) Programme in Indonesia is researching the learning outcomes of 1,500 Grades 2–5 primary school students during the pandemic in Bukittinggi.

The people of Bukittinggi are known for prioritising education. They, for example, have the expression of “let there be no food, as long as there is no lack of knowledge”.

The majority of students there have minimum communication with their teachers after schools were closed, but they continued to study 6 days per week with their parents while at home. This culture had existed since before the pandemic and has intensified during the pandemic.

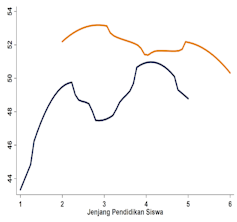

Our research even revealed that Bukittinggi students’ numeracy and literacy test scores during distance learning in 2020—measured using RISE-SMERU's instruments—were higher than during in-person learning in 2019.

Student test results in Bukittinggi. The yellow line shows 2020, while the blue line shows 2019. (SMERU Research Institute)

Surprisingly, although the test results of students whose parents have lower educational attainment were below those of students whose parents are highly educated, students from all socio-economic groups have experienced an increase in achievement during the pandemic.

In fact, the most significant increase was seen in lower-class students whose parents have lower educational attainment—catching up with students from higher economic groups.

This research is not final, and we are still waiting for many more interesting findings.

Thus far, there are indications that so long as parents have a strong commitment and support to be more engaged with their children’s education while learning from home, the results will be outstanding.

Cultivating a culture of being more engaged with children at home

Unfortunately, these eagerness and practices have not become the habits of community groups in many other areas.

As an effort to break this ground, RISE-SMERU initiated a campaign to encourage active involvement of parents in their children's education. This programme is in collaboration with the Kebumen District Education Office in Central Java.

Starting from February 2020, every month we sent letters and leaflets to parents of students in 65 primary schools, inviting them to be more involved in their children's learning.

The themes of the leaflets were good practices that parents could adopt—including some important lessons from the SMERU study in Bukittinggi.

Among them were learning from home guidelines, creating a comfortable and calm atmosphere for children to study, how to encourage children to learn, reading with children, how to communicate with teachers, and others.

RISE-SMERU researchers are currently analysing this impact.

If we could replicate the willingness and the culture of parental engagement in Bukittinggi, this method could be a good model for education policy makers throughout Indonesia.

Schools can play roles by working with parents

The loss of learning, along with the Merdeka Belajar movement initiated by Minister Nadiem, remind the public that students learn at different paces.

Teachers in schools play a role in identifying their different achievements through regular assessments, and then providing appropriate learning materials so that students can catch up. Our study at J-PAL, for example, examines an assessment method called Teaching at the Right Level (TARL) that has been tested for two decades in India.

However, the above process does not entirely occur at schools that teachers need to communicate with parents on a regular basis.

In this case, parents play a role in continuing their children’s learning process according to the teacher's direction, particularly in the midst of the transitional blended learning of school and home.

However, parents have different capacities and time to be more involved with their children’s education due to their work.

Stakeholders need to identify appropriate supports for parents while monitoring student learning. A study from J-PAL, for example, found that simple tools such as short text messages to telephone were effective in strengthening engagement of teachers and parents.

However, the opposite is also an option—bringing parents closer to schools and classrooms.

In the late 1980s, the school where one of our children studied in the United States invited parents in a programme of rotating class visits.

The impressive thing we saw was the love of students for their teachers. When they arrived at school, the first thing every child did was look for their teacher to say good morning and show their presence. The teacher would then greet them in a friendly manner.

Meanwhile, in Indonesia, students tended to avoid running into their teachers—perhaps they still do today.

More importantly, such visits allow parents to gain experience and understanding of the dynamics in their children's classrooms. Parents receive information about what is being taught and are aware of class instructions and plans. Conversely, teachers will get valuable feedback.

Ultimately, this strengthens the bond between home and school.

The education office at the district/city or school level, for example, can initiate such a visit programme. A classroom accommodates an average of 30 students. If every year a class provides 30 weeks to invite parents in rotation, and three days are allocated to each week, then in a year, each parent has three opportunities to observe the teacher teaching their children.

This pandemic is a momentum to reflect on changes to education strategies and policies.

In addition to improving the education concept to be more in favour of each child’s development, this period also opens insight into the crucial active role of parents in the students’ learning at home.