Foto ilustrasi: Novita Eka Syaputri

.

This article is republished from The Conversation Indonesia (TCID) and is part of the TCID article series to commemorate Indonesian Independence Day on 17 August 2021.

.

Indonesia's educational attainment remains low in recent years—based on world and national standards, despite the fact that every year the government allocates 20% of the state budget for education, as mandated by law.

Indonesia ranked 7th from the bottom of nearly 80 countries in the 2018 global assessment of Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA); only 1 of 3 Indonesian children met the minimum level of reading ability. Whereas the 2015 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) report also showed that 27% of Indonesian children in Grade 4 had inadequate basic mathematics knowledge.

Numerous analyses at the national level also mentioned how the weak competence of teachers and education policy in the regions had caused Indonesian students’ learning achievement to remain low.

To understand this stagnant educational attainment more deeply, our latest research for the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) programme seeks to analyse the learning profile of children in Indonesia.

We mapped students' numeracy ability using data from the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) for the period of 2000–2014.

Unfortunately, we found some bad trends in national educational attainment. In fact, our research revealed that the learning outcomes of Indonesian children in 2014 were lower than in 2000.

Moving up a grade but not learning

In conducting the analysis, our team only used IFLS data available until 2014. The next survey data scheduled for 2020 had to be delayed due to the pandemic.

Nevertheless, our research revealed at least three alarming trends related to the learning outcomes of Indonesian children.

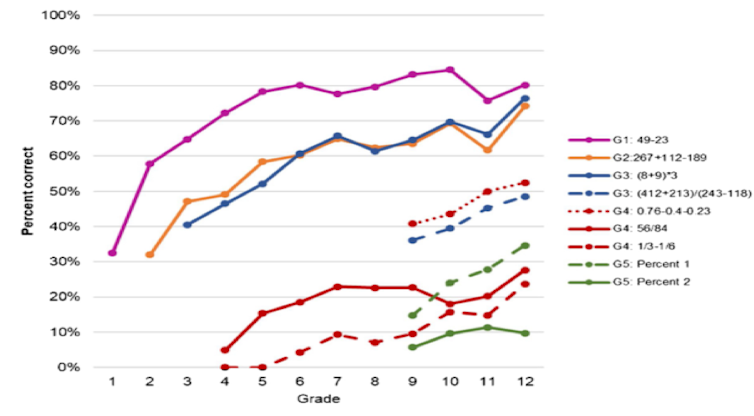

First, our analysis of the 2014 IFLS showed that many school children were unable to solve the mathematical problems that they should had mastered at a lower grade level.

In Figure 1, for example, only two-thirds of children in Grade 3 were able to solve the subtraction problem of “49-23” correctly. This is actually equivalent to the numeracy skill of children in Grade 1.

The low children’s learning achievement is increasingly seen in more difficult questions.

For example, only approximately 35% of students in Grade 12 were able to correctly answer a Grade 5 question on calculating interest—seven grades below their level.

Figure 1. The ability of students at each level to answer questions. The horizontal axis shows the level of education, while the vertical axis shows the percentage of students who could answer the questions. G1-G5 are the types of questions that students in Grades 1–5 should be able to answer.

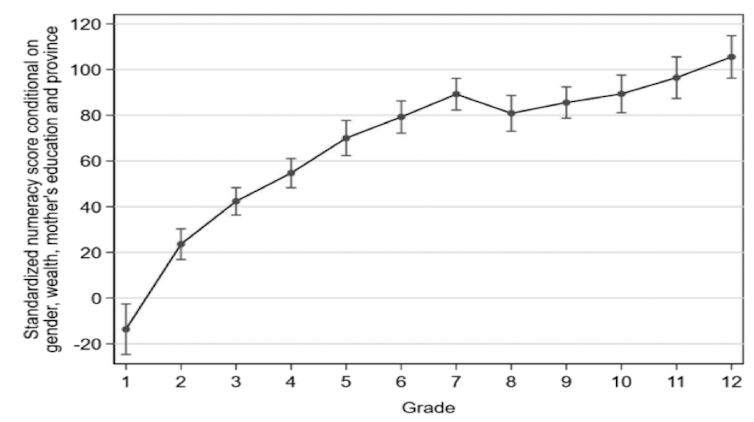

Second, we also observed that the improvement of children’s ability decreased as they moved up to a higher grade level.

Figure 2 shows that children in Grades 1–6 experienced a significant improvement in numeracy skills. However, the trend of this improvement slowed down and tended to flatten after Grade 7 and above.

From this, we may conclude that the children's abilities did not experience a significant improvement when they were growing up and studying at the junior secondary school and senior secondary school levels.

Figure 2. Improvement of children's numeracy skills as they move up the grades

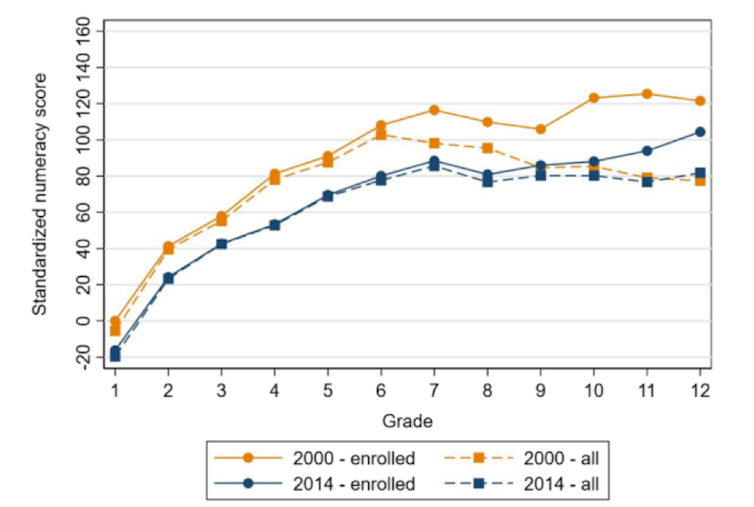

Third, when comparing IFLS data in 2014 with the 2000 data, we found that children's numeracy skills in 2000 were relatively higher compared to children at the same level 14 years later.

We can see in Figure 3 that the children’s achievement at each level in 2014 was consistently below the achievement in 2000.

This conclusion applies both when we analysed only the group of children who were in school, and when we also included children of that age who did not attend school.

This means that at least from 2000 to 2014, the educational attainment of Indonesian children actually decreased.

Figure 3. Comparison of students’ educational attainment at each level between 2000 (yellow line) and 2014 (blue line).

Our analysis using available data has yet to shed more light on the factors that caused these negative trends in children's learning in Indonesia.

However, we have hypotheses of factors that drove this decline in learning achievement—at least for numeracy skills.

One of which is the modification of numeracy content since the 2004 Curriculum.

This modification has reduced the learning hours for numeracy from 8–10 hours (Curriculum 1994) to 5 hours per week, affecting students' numeracy and numeracy-based problem-solving abilities.

Furthermore, a policy of the Ministry of Education and Culture (MoEC), which since 2003 has continued to reduce the weight of school exams on graduation, and is more concerned with the National Examination, has also encouraged students to study only for the sake of graduation rather than sharpening their knowledge and thinking skills.

Besides, there is also a trend in Indonesia where students [continue to move up grades] even though their abilities are inadequate.

Here, inaccurate assessments and evaluations of learning outcomes have caused students to lose the opportunity to strengthen their understanding of materials they have not mastered at their previous levels.

The emergency of the nation's childrens’ learning achievements

This study’s results should be a yellow light for all stakeholders in the education sector to immediately make improvements.

Although this study only reviewed the learning outcomes between 2000 and 2014, I believe that the above negative trend is likely to continue from 2015 to today. The COVID-19 pandemic could further exacerbate Indonesian students’ lagging in learning.

Both central and local governments need to change the education policies, which to date tend to be driven by political factors—from the habit of showing off national achievements on children's access to schools to being trapped in the politics of improving teachers’ welfare during the election period.

It is time for the government to seriously think about policies that are truly oriented towards improving the quality of children's learning in schools.

For example, the teacher recruitment system, particularly in public schools, should be based on indicators that measure their abilities to teach students rather than meeting the State Civil Apparatus (ASN) quota.

Furthermore, learning evaluations by schools—both through assessments by teachers and through examinations—should be carried out with a focus on mapping the students’ achievements and as a basis for teachers to develop their learning strategies, rather than merely a ranking tool. In recent years, for example, the average score of the National Examination is often used only to rank schools or to determine the amount of the Regional Incentive Fund from the central government.

Parents and teachers should also change the old perspectives that children go to school to get high test scores. A good learning process should be to understand the concept completely without having to compete.

![]()